Here’s our psilocybin-assisted therapy guide to discover the highlights of psilocybin research and treatment approaches. We’ll take you the therapeutic timeline, common effects, psilocybin-assisted therapy study designs, clinical trial findings, and participant reports. When you are ready to learn more, take one of our online courses!

Drug Class

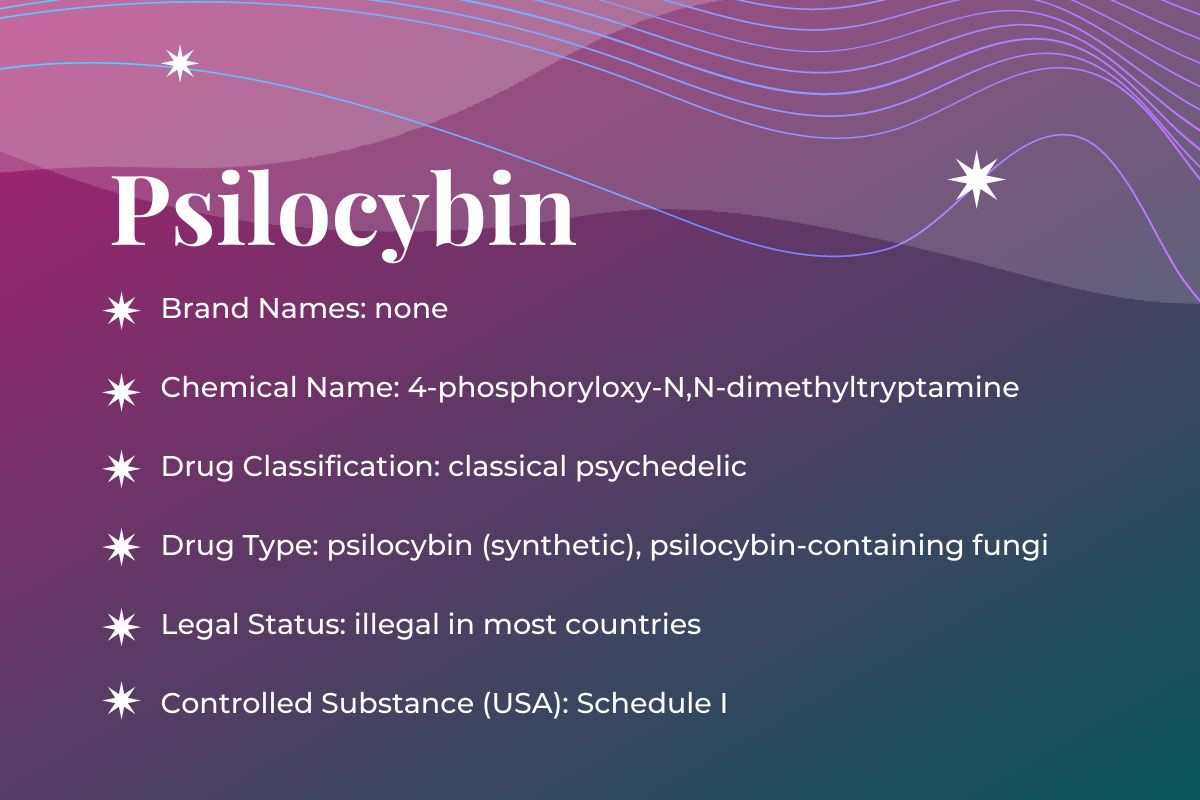

Psilocybin (C12H17N2O4P) is an indole alkaloid chemically similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT) making it a member of the tryptamine class of classical psychedelics.

What is Psilocybin?

Psilocybin is found in over 200 species of mushrooms. When psilocybin is ingested, it is rapidly metabolized to psilocin. It is psilocin that activates receptors in the brain to induce visionary effects. Both psilocybin and psilocin can be synthesized in a laboratory.

As noted above, psilocybin is an indole alkaloid that bears a strong resemblance to serotonin. An indole is an aromatic double-ring system containing a nitrogen atom in the five-membered ring, which is fused to a benzene ring. A tryptamine is an indole molecule with an ethylamine group attached to carbon 3 of the 5-membered ring.

Furthermore, psilocin is a high affinity partial agonist that activates the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor (<40% activation). Psilocin binds to other types of serotonin receptors too, but ultimately, the hallucinogenic effects are due to activation of the 5-HT2A receptor. Other classical psychedelics bind to this same receptor.

From the Streets to Psilocybin Assisted Therapy Offices

Like its other psychedelic companions, the journey of psilocybin mushrooms into, out of, and back into, the American psyche has been one heck of a trip. The full history of psilocybin mushrooms will be discussed later. For now, let’s focus on the “back into the American psyche” part, both literally and figuratively.

Even though psilocybin mushrooms have been used in Central and South American cultures, as well as others around the world, for countless years, psilocybin was largely unknown to the West up until the 1950s. An investment banker, R. Gordon Wasson, came upon psilocybin while in Mexico thanks to a famous Indigenous curandera, Maria Sabina.

Psilocybin, like its cohort LSD, got caught up in the psychedelic panic 50 years ago. Now, decades later, it’s resurfacing for psychotherapeutic purposes. Yes, if you haven’t already read or seen it somewhere else, psilocybin mushrooms can be good as mental health treatments in specific contexts. Yes, the same “magic mushrooms” once demonized, are now returning with legitimacy.

Psilocybin has enjoyed a boost of exposure and research thanks to the psychedelic evolution happening right now. After being pushed underground for many decades, psilocybin slowly began to mushroom in scientific circles. Similar to MDMA, the consistent and persistent work of a handful of people on the fringes of science allowed psilocybin to become mainstream once again.

In 1990, Dr. Rick Strassman re-commenced clinical research into classical psychedelics with his legendary Phase 1 studies of N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in healthy volunteers.

The Heffter Institute was established by researchers David Nichols PhD, Charles Grob MD, Dennis McKenna PhD, and colleagues in 1993 to “promote research of the highest scientific quality with classic hallucinogens and related compounds (sometimes called psychedelics).”

Follow your Curiosity

Sign up to receive our free psychedelic courses, 45 page eBook, and special offers delivered to your inbox.Therapeutic Timeline

- 1990s – Heffter Institute begins funding human safety studies.

- 1990 – Dr. Rick Strassman begins a Phase I DMT dose-response study.

- 2001 – Phase 1 clinical trial of psilocybin in healthy volunteers commenced.

- 2001 – MAPS conducts first FDA-approved study in 25 years of psilocybin for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- 2004 – Phase 2 randomized-controlled clinical trials of psilocybin-assisted therapy for anxiety and depression in terminal cancer patients commenced.

- 2010s – First human brain imaging studies of psilocybin at Imperial College in collaboration with the Beckley Foundation.

- Phase 2 open-label clinical trials of psilocybin-assisted therapy for:

- treatment-resistant depression at Imperial College London

- anxiety associated with advanced-stage cancer at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Johns Hopkins University, and New York University

- nicotine dependence at Johns Hopkins University

- alcohol dependence at University of New Mexico and New York University

- anorexia nervosa at Johns Hopkins University

- 2018-2019 – Phase 2 trials, sponsored by Usona Institute and Compass Pathways Ltd, underway in the USA and Europe studying psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression received Breakthrough Therapy status. Ongoing investigations could potentially result in FDA and EMA approval of psilocybin-assisted therapy for clinical implementation by 2027.

- Ongoing – Other current trials are investigating psilocybin for alcohol use disorder, depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s Disease, existential distress in palliative care, headache disorders, OCD, anorexia, and body dysmorphic disorder. New trials are starting all the time, check here for a complete list of psilocybin studies.

What is Psilocybin Assisted Therapy?

A growing number of public and private psychedelic companies have interests in psychedelic-assisted therapy, and a number of these are developing mushroom and synthetic products. These developments will broaden access to psilocybin-assisted therapy, although pricing barriers to entry are yet to be known. Regardless, psilocybin-assisted therapy may soon become an accepted branch of psychotherapy.

Psilocybin-assisted therapy involves ingesting psilocybin while exploring a specific, previously set intention, with the goal of healing and transformation. Researchers and clinicians often describe three distinct therapy phases: preparation, the acute psychedelic experience, and integration. The non-psychedelic elements of this approach are essential for both effectiveness and safety.

Various approaches to preparation have been developed, from diet to psychotherapy. In clinical trials, participants will typically attend a number of talk therapy sessions with two trained therapists or guides who will be in attendance during the psychedelic session. Safety and rapport are developed during this time, and the nature of the individual’s struggles are explored.

The guides will prepare the patient for the psychedelic session in a number of ways, with a particular emphasis on curiosity and ways to remain open to challenging experiences (“If you see a door, go through it”; “If you meet something scary, walk towards it and ask, ‘what do you have to teach me?’”). While challenging experiences are considered by many who work in the field to be integral to the therapeutic and personal benefits that follow, the so-called ‘bad trip’ is often borne out of an attempt to avoid the experience and can be mitigated by an open and trusting approach.

During the psilocybin session, ‘set’ and ‘setting’ are considered paramount. ‘Set’ refers to mindset. Mindset is a complex mix of more transient phenomena like expectation and mood and more enduring phenomena like personality and past experience. ‘Setting’ refers to the context or environment in which the session takes place, including basic factors like the comfort and aesthetic quality of the room and more complex factors like the quality of the relationship with the clinicians and the mood they help to set.

While many modern clinical trials occur within hospitals or research institutes, the session rooms are made to appear as comfortable living rooms. There are typically two therapists in attendance. The patient can sit or lie on a couch, is often encouraged to wear a sleep mask to go inwards, and, at times, listen to a carefully selected playlist of music. Oral ingestion of a capsule of synthesized psilocybin is the route of administration in clinical settings. The participant ingests a dose (low: 10 mg, medium: 20 mg, high: 30 mg or above) at the start of the session. The psilocybin effects generally last 3-6 hours, but the therapeutic session can last for 6 to 8 hours.

A common therapeutic approach during psychedelic sessions is to be non-directive.

Attentive but usually silent, supporting the emerging process and offering assistance and guidance if needed. In addition to listening and responding to the participant when they speak, the guides offer little analysis of the material but may ask questions for the person to reflect on what is coming up for them. In clinical trials, participants have 1-3 psilocybin sessions.

Immediately after the psilocybin session and in the following days, a process of integration is facilitated by the guides. During these conversations, the person has the opportunity to process, make sense of, and give meaningful expression to their psychedelic experience.

What Does Psilocybin Do to My Brain (Pharmacology)?

Psilocybin is easily converted within the body to the simpler compound, psilocin via dephosphorylation. Psilocybin is, therefore, a “prodrug” of psilocin. Psilocin acts to stimulate (is an agonist of) the 5-HT2A receptor to induce the psychoactive effects.

Psilocin is a relatively unstable compound, being susceptible to oxidation due to its exposed 4-hydroxy functional group. Psilocybin is substantially more stable as the hydroxyl oxygen atom is protected by a phosphate group.

Psilocybin and psilocin are highly water-soluble, hence orally available, and are quickly absorbed into the bloodstream through the stomach wall. The 4-phosphoryloxy group of psilocybin is quickly hydrolyzed to form psilocin under physiological conditions. Psilocin is metabolized by monoamine oxidase (MAO-A & MAO-B) throughout the body, being oxidized to 4-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. In healthy humans, psilocybin/psilocin has a half-life of 2-3 hours, with non-ordinary states of consciousness typically lasting 3-6 hours.

Agonism at the 5-HT2A receptor is thought to be most directly responsible for the classical psychoactive effects of changes in perception, visual patterns, discrete images, euphoria, distorted sense of time, synesthesia, emotional lability, and sometimes mystical or spiritual experiences.

For a quick look at how psilocybin mushrooms affect the brain, please watch below:

For a complete pharmacological briefing on psilocybin, please read the “Pharmacology of Psilocybin” from Addiction Biology written by Passie, Seifert, et al.

Psilocybin Positive Effects

The following positive effects of psilocybin are the most common: visual distortions, vivid imagery with eyes open or closed, auditory and visual hallucinations, sensory synesthesia, feelings of expansiveness, feelings of oneness and connection with others and the universe, heightened emotions, transcendence of space and time, ego dissolution, mystical experiences, altered cognition, Introspection, and insightfulness.

Through clinical trials, psilocybin has been proven to have a wide variety of benefits. One of the institutions leading the way in psilocybin research is Johns Hopkins University. At Johns Hopkins, Dr. Roland Griffiths heads the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. Dr. Griffiths has produced a large amount of research on psilocybin. In fact, Dr. Griffiths and some colleagues found that “emotions and brain function are altered up to one month after a single high dose of psilocybin.”

Watch Dr. Griffiths deliver this talk about “Magic mushrooms’ amazing positive effects.”

Psilocybin Negative Effects

Like all drugs, psilocybin can induce side effects. The environment where a person takes psilocybin can significantly impact the experience. The following negative effects of psilocybin are the most common: panic attacks, anxiety, confusion, paranoia, dysphoria, irrational and reckless behavior, impaired concentration and focus, disordered thinking, dizziness, disorientation, restlessness, muscle weakness, nausea or vomiting, light sensitivity, pupil dilation, flashbacks, and headaches.

From a physical standpoint, psilocybin is exceptionally safe. There is no established toxicity in humans. Psilocybin mushrooms may precipitate or exacerbate (generally pre-existing or incipient) mental health conditions, such as psychosis, in non-clinical or unsuitable clinical settings. Outside of clinical and medical contexts, improper mushroom usage can lead to accidents caused by impaired judgment, as well as poisoning as a result of the misidentification of look-alike mushrooms.

However, adverse effects can include transient fear and/or anxiety, sometimes panic, an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, paranoia, and risk of psychosis – generally in susceptible individuals and/or with extended use.

Psilocybin Contraindicated Medications and Conditions

Overall, psilocybin has a low-risk profile and few contraindications. The following are the notable exceptions and contraindications.

One of the primary concerns is uncontrollable hypertension (high blood pressure). In psilocybin research trials, people with systolic blood pressure greater than > 140 and diastolic blood pressure greater than > 90 are generally excluded. Psilocybin is known to increase blood pressure and heart rate, so people with cardiovascular issues are screened out.

No data exists to suggest that pregnant women or women who are nursing are at risk during psilocybin use. However, out of an abundance of caution, it is recommended that they abstain from trial studies. Women wishing to participate in trials are encouraged to implement proper birth control methods.

Certain psychiatric conditions pose contraindicated risks. These include schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which extends to first-degree relatives that cause would-be trial applicants to be screened out. According to this paper published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, “Contraindications include people with borderline personality disorders or schizophrenic tendencies.”

As reported in the journal Molecules:

Another risk is the possibility of exacerbating psychotic symptoms. As a result, having psychotic disorders such as schizophrenic tendencies is a contraindication for undergoing psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, particularly psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy.

Psychedelics have the potential to exacerbate the following psychiatric symptoms: paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, mania, and depression.

Psilocybin may prolong symptomatic amplification days, weeks, or even months, particularly with higher dosages. Although rare, cases of suicidal ideation and auto-mutilation have occurred in patients with mental or psychiatric disorders.

Various reports suggest that people with antisocial and/or borderline personality disorders, high scorers in the rigidity personality trait, people with labile moods, and those under the influence of alcohol are all at higher risk for negative experiences with psilocybin. Not enough data related to psychiatric contraindications exists yet to determine if specific risks can be mitigated through specific protocols.

Lastly, in rare cases, a contraindication known as “serotonin syndrome” may pose a risk. Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening syndrome that occurs when there is an overabundance of serotonin in the body. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome include autonomic (hyperthermia, hypertension, tachycardia, sweating, pupil dilation, flushing), cognitive (agitation, confusion, hyperactivity, hypomania), neuromuscular (overactive reflexes, stiff muscles, muscle contractions, tremor).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may put people at high risk when used in combination with psilocybin. Although serotonin syndrome is not well understood and more research is needed, there seems to be a direct effect on the same 5-HT2A receptors that psilocybin also targets. According to Mind Foundation:

The precise pathophysiology of serotonin syndrome is not completely understood, but it appears to result from an excess in serotonin neurotransmission. It is not linked to a single serotonin receptor, even though it is suggested that 5-HT2A receptors substantially contribute to the condition.

Despite a lacking a fuller body of research on serotonin syndrome, caution is strongly advised when combining SSRIs with psilocybin. SSRIs that pose risks include: Citalopram (Celexa, Cipramil), Escitalopram (Lexapro, Cipralex), Fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem), Fluvoxamine (Luvox, Faverin), Paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat), and Sertraline (Zoloft, Lustral). Furthermore, research suggests:

Since we don’t know exactly how this boost in serotonin levels has an antidepressant effect, it’s hard to anticipate how SSRIs might interact with psilocybin. However, since both substances work on the serotonergic system, there is likely to be some sort of overlap.

As of 2016, 3 cases of serotonin syndrome as a result of psilocybin mushroom poisoning were documented in a peer-reviewed journal.

Psilocybin History and Law

- 1955 – June, R. Gordon Wasson becomes the first Westerner to ingest psilocybin mushrooms in a sacred ritual performed by Maria Sabina in Mexico.

- 1950-1960s – Awareness of psilocybin spread in the West in the late 1950s and accelerated as the psychedelic era took hold in the 1960s.

- 1960 – The Harvard professor and later LSD proponent Dr Timothy Leary was introduced to Psilocybe mushrooms in Mexico.

- The 1960s – As the benefits of psilocybin for treating anxiety, depression, and other disorders surface, the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz markets psilocybin in many countries, including the United States (US), under the trade name Indocybin.

- 1960-1963 – Leary and his research group, the Harvard Psilocybin Project, studied psilocybin – both formally and informally. Nearly 4,000 psilocybin doses are ingested by almost 600 subjects.

- 1966 – Sandoz discontinues manufacturing and marketing of Indocybin.

- 1971 – Psilocybin, along with many other psychedelic compounds, was scheduled through the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Psilocybin saw relatively limited therapeutic use in the USA, as interest in the therapeutic applications of LSD was already established. The use of Psilocybe mushrooms went underground and continued largely recreationally, but possibly also therapeutically, to the present day.

Legal Status

It’s complicated. Psilocybin laws show great variance internationally as well as within the United States. It is interesting to note that specific species of mushrooms themselves are not illegal however the psychoactive chemical is.

Internationally: Psilocybin and its active metabolite, psilocin, are listed as Schedule I drugs under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Across most of the world, especially the West, psilocybin is illegal, save for a few countries granting decriminalization. Some of the exceptions where psilocybin is legal include the Bahamas, Brazil, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Nepal, Netherlands (as truffles), and Samoa.

Nationally: Psilocybin and psilocin are Schedule I drugs under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. However, in recent years, various states and cities have voted to decriminalize psilocybin mushrooms. Cities like Denver, CO, Oakland, CA, Santa Cruz, CA, Ann Arbor MI, Cambridge, MA, Washington D.C. and others, have decriminalized psilocybin mushrooms. In Oregon, a state initiative was passed in 2020 to allow for the legal consumption of psilocybin mushrooms in supervised settings. A different Oregon measure passed the same year to decriminalize all drugs and mandated more emphasis on addiction treatments than criminalization for personal possession of drugs. In 2024, Oregon rolled back the decriminalization measure for personal possession of all drugs, but legal psilocybin centers were not part of this legal change and continue to operate.

Psychotherapeutic Applications for Psilocybin

Psilocybin is thought to be an effective treatment for disorders related to rigid modes of thinking – those disorders based on habits & biases. Trials are ongoing, so effectiveness isn’t yet scientifically proven. Disorders showing promise through ongoing trials for psilocybin-assisted therapy include anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, addictions, and headache disorders.

The possibilities for therapeutic applications of psilocybin range far and wide. Again, Dr. Roland Griffiths and his colleague at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Matthew Johnson, published a paper titled “Potential Therapeutic Effects of Psilocybin.” In this paper, they found:

For mood and anxiety disorders, three controlled trials have suggested that psilocybin may decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in the context of cancer-related psychiatric distress for at least 6 months following a single acute administration. A small, open-label study in patients with treatment-resistant depression showed reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms 3 months after two acute doses. For addiction, small, open-label pilot studies have shown promising success rates for both tobacco and alcohol addiction.

Other researchers have found that:

…a one-time, single-dose treatment of psilocybin, a compound found in psychedelic mushrooms combined with psychotherapy, appears to be associated with significant improvements in emotional and existential distress in people with cancer. These effects persisted nearly five years after the drug was administered.

The worlds of psychology and psychiatry and beginning to catch on to the benefits of psilocybin. This paper notes that “Drugs, such as psilocybin and LSD, classified as entheogens, are associated with introspection and new insights, shifts of perspective, and reframing of experience and relationship to others and the world.”

For an excellent, in-depth look at how psilocybin-assisted therapy works, please have a look at this psilocybin trial led by Dr. Robin Carhartt-Harris at the Imperial College of London.

The Imperial College of London has been producing a lot of quality research regarding psilocybin-assisted therapy. Here, clinical psychologist Dr. Rosalind Watts discusses how magic mushrooms can beat depression.

Finally, here’s another talk from Dr. Roland Griffiths, discussing how psychedelics can relieve suffering, especially for those dealing with terminal illnesses.

And here is Dr. Griffith’s colleague from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, Dr. Matthew Johnson, giving a lecture on the therapeutic effects of psilocybin.

Testing & Analysis (Clinical Trials)

Here’s a sampling of the relevant testing and analysis from psilocybin-assisted therapy trials.

Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms

Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up

Pilot Study of Psilocybin Treatment for Anxiety in Patients With Advanced-Stage Cancer

Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use

Potential Therapeutic Effects of Psilocybin

Psilocybin-Occasioned Mystical Experiences in the Treatment of Tobacco Addiction

Effects of Psilocybin in Advanced-Stage Cancer Patients With Anxiety

Psychopharmacology of Psilocybin in Cancer Patients

Psilocybin Cancer Anxiety Study

Psilocybin-facilitated Smoking Cessation Treatment: A Pilot Study

Psilocybin for the Treatment of Cluster Headache

Psilocybin for the Treatment of Migraine Headache

Effects and Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin in Alcohol Dependence

For a complete list and map of psilocybin studies, please take a look here at our clinical trial listings.

Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy Testimonials from Patients

Some clinical trial participants have volunteered to go public with their journey and talk about how psilocybin-assisted therapy helped them heal. The best way to learn about the potential of psilocybin as a medicine is the people who’ve used it to heal.

Individual Experiences in Four Cancer Patients Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy

Here are some quotes from cancer patients following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy:

With regard to his increased spirituality, Victor stated, “I am convinced beyond any doubt that there is a spiritual realm…The spirit guide showed me a world that I believe to be very, very real.” When asked how the experience changed his attitude toward his cancer, he responded, “It is what it is…it’s not worth worrying about things you can’t change.”

“There is nothing to fear after you stop being in your body …it’s absolutely no hell or heaven, it’s just nothing to be afraid of.” He also detailed being surrounded by an “overwhelming feeling of love… I felt the urge to let people know to stop silly things and that nothing matters but love.”

She spoke about feeling pain in her abdomen, where her cancer was, and experienced this as her “umbilical cord to the universe.” She expressed, “this was where my life would be drained from me some day and I would surrender willingly when my time came.” Though Chrissy experienced a sense of being at peace with death, she went on to explain that she “chose to live,” and that the experience helped her reach this decision.

On the first occasion, she said, “I went into this black area and it was just wonderful… I just thought to myself… I think this might be what people experience when they die.” Her second encounter with death included seeing, “This brick thing that was a lot of bricks, and I realized this was a kind of crematorium… I was just part of this big beautiful world… and that’s what’s going to happen when I die… maybe death is a beautiful thing.”

Here are some quotes from patients after experiencing psychedelic treatments for psychiatric disorders:

“(The psilocybin) just opens you up and it connects you … it’s not just people, it’s animals, it’s trees—everything is interwoven, and that’s a big relief … I think it does help you accept death because you don’t feel alone, you don’t feel like you’re going to, I don’t know, go off into nothingness. That’s the number one thing—you’re just not alone.” [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

“(During the dose) I was everybody, unity, one life with 6 billion faces, I was the one asking for love and giving love, I was swimming in the sea, and the sea was me.” [psilocybin, depression].

“Excursions into grief, loneliness and rage, abandonment. Once I went into the anger it went ‘pouf’ and evaporated. I got the lesson that you need to go into the scary basement, once you get into it, there is no scary basement to go into (anymore).” [psilocybin, depression].

“A veil dropped from my eyes, things were suddenly clear, glowing, bright. I looked at plants and felt their beauty. I can still look at my orchids and experience that: that is the one thing that has really lasted.” [psilocybin, depression].

Here are some final quotes courtesy of Johns Hopkins University:

After their session, one participant wrote: “I was reveling in the undeniable feelings of infinite love. I said [to myself], ‘I am love, and all I ever want to be is love.’ I repeated this several times and was overwhelmed with the intensity of the love. I was aware of tears flooding my eyes at this point. All the other goals in life seemed completely stupid.”

“Once I was past the darkness, I began to feel an increasing feeling of peace and connectedness…An intense feeling of love and joy emanated from all over my body and I can’t imagine feeling any happier. I knew that the worries of everyday life were meaningless and that all that mattered were my connections with the wonderful people who are my family and friends.”

“Everything is swept up into a climactic epiphany of love as the universal essence and meaning of all things. The journey of spirit coming to itself, revealing to itself its own inner mystery, is nothing but the self-realization of love.”

“The purpose of all of us here together is to be constant reminders to each other of Who We Really Are.”

Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy Testimonials from Therapists

So, what do therapists have to say? The picture wouldn’t be complete without hearing from a therapist’s perspective, especially in regard to a not-yet-legal treatment.

That video is taken from our Foundations in Psilocybin Safety, Therapeutic Applications & Research course. The course is your guide to exploring psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy and learning about the latest clinical protocols and trial findings. Differing hypotheses regarding the effects of psilocybin in the brain are also covered.

If you’re interested in learning more about the course, we invite you to learn more. Read below about how you can get the course syllabus.

Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy Training Opportunities

Ready to get started? We’re offering a free guidebook and online courses.

Click through here, give us your email, and we’ll send you a FREE PDF of The Little Book of Psychedelic Substances and free psychedelic courses.

When you are ready to go deeper into the science and therapeutic approaches, enroll in our evidence-based, self-paced course on Psilocybin (CE/CME credit available)! This course is perfect for health professionals, neuroscience and psychology students, and anyone who wants in-depth knowledge of psychedelics.