Drug Class

Mescaline is a naturally occurring phenylethylamine found in several cacti species that grow in regions of the United States and Mexico. Phenylethylamines are compounds that work on the sympathetic (also known as the ‘fight or flight’) nervous system. There are many types of phenethylamines, including the endogenous (produced by the human body) neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine, as well as non-psychoactive pharmaceuticals like salbutamol (commonly used in inhalers for asthma) and phenylephrine (a nasal decongestant). Examples of psychoactive phenethylamines include amphetamines (used for the treatment of ADD/ADHD), MDMA, and mescaline.

This diverse group of substances all share the same chemical backbone and have a similar overall molecular structure. Although chemically related to dopamine and norepinephrine, psychedelic phenethylamines also interact with the serotonin pathway by stimulating serotonin receptors and increasing the release of serotonin. Mescaline has unique effects compared to serotonin 2A receptor agonists like psilocybin and, in many ways, can induce effects similar to adrenaline, such as nausea and increased heart rate. The experience and side effects of mescaline are a cross between the classical psychedelics and amphetamines1,2.

What is Mescaline?

Mescaline is a naturally-occurring psychoactive alkaloid found in several cacti, including the Peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii), San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi), and Peruvian Torch cactus (Echinopsis peruviana). The Fabaceae bean family also produces small quantities of mescaline.

Mescaline is one of the four main ‘classical’ psychedelics (the three in the group – LSD, DMT, and psilocybin are classified as tryptamine alkaloids). Mescaline is unique compared to other classical psychedelics due to its distinct molecular structure, effects, and classification as a phenylethylamine3. However, it binds to similar receptors as other psychedelic drugs.

The mescaline trip is longer compared to most other psychedelic substances. The trip can last between 9 to 12 hours. Beyond kaleidoscopic visuals, mescaline can alter tactile sensations and the perception of space and time4.

Interestingly, mescaline consumed as cacti may act in a similar way to cannabis, where multiple active compounds contribute to an ‘entourage effect,’ meaning the experience is generated through complex augmentation and synergistic interactions of the individual components.

Peyote, in its natural form, contains dozens of different types of phenylethylamine alkaloids, some of which are pictured above. It is possible that different kinds of cacti containing various constituents could result in distinct experiences, similar to how cannabis strains produce a variety of subjective effects5.

Lophophora williamsii contains about 0.4% of mescaline by weight (fresh, undried) and up to 3-6% dried4. This “cocktail of compounds” may enhance or alter the pharmacology of mescaline. The various psychoactive compounds are found in different areas of the plant, with some being active on their own.

For example, hordenine is a N,N-dimethyl derivative and has activities in the human body similar to the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine. Hordenine can cause increased blood pressure, respiration, and heart rate6.

Pellotine is the second most abundant alkaloid in Lophophora williamsii (and the most abundant alkaloid in other Lophophora species). It was marketed as a sedative/hypnotic by Boehringer & Sohn in Germany but was subsequently discontinued after the advent of barbiturates around a century ago. Anhalinine is a stimulant alkaloid that can be isolated from the cactus as well7.

We’ll further describe the effects of mescaline later in this article. But before we do, let’s dive into mescaline’s rich history and its traditional use by Indigenous peoples,

Mescaline: History and Culture

Mescaline is believed to have been consumed by humans for more than 5000 years8,9. Radiocarbon dating of peyote found in a cave above the Rio Grande in Texas suggests its use dates back to at least 5,700 years, making it the oldest known psychedelic agent in North America9. It has a rich history of use in various Indigenous tribes in South America, Mexico, Texas, and other parts of the United States (described in detail below).

In traditional and ritualistic practices of Indigenous communities, mescaline is derived from fast-growing San Pedro cacti and slow-growing peyote cacti. Peyote cacti were first introduced to Western culture when Spanish people arrived in Mexico in the early sixteenth century. The active component was isolated in 1895 by the German chemist Arthur Heffter, who coined the name “mescaline”. Surprising to most, mescaline predated the discovery of LSD as well as the isolation of psilocybin from “magic mushrooms”. The introduction of mescaline “led the way in early Western medical experiments using psychedelic agents”. Later, in 1919, the substance was synthesized in the laboratory, and many retreat centers offered it.

Author Albert Huxley and psychiatrist Humphry Osmond were of the early pioneers who experimented with the cacti. Huxley’s mescaline experience was so powerful that he opened his book “The Doors Of Perception” with an account of his first mescaline trip he undertook in 195310. After Huxley introduced Osmond to the substance, he wrote in a letter in 1954 to Huxley, “To fathom hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic,” which led the two to come up with the term psychedelic (“mind-manifesting”).

Along with many writers and scientists, mescaline attracted the attention of the famous chemist Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin and his therapist wife, Ann Shulgin. Experiences with mescaline informed their book PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story (PiHKAL is an acronym for ‘Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved’). Sasha’s explorations with psychedelic substances began with his first mescaline trip in 196011.

Here is a conversation about mescaline with Ann and Sasha Shulgin:

Mescaline: Indigenous Traditions

Indigenous communities in North and South America have used mescaline-containing cacti in their religious and spiritual ceremonies for millennia, facilitating communication with deities, ancestors, and spirits. The Huichol people of Mexico, for example, use mescaline in their peyote ceremonies as a way to connect with the spirit world and gain insights into the nature of Being and the mysteries of the universe. Other traditional uses of cacti containing mescaline include healing and divination. Today, mescaline is used recreationally for psychedelic effects, for healing experiences and consciousness work, and in continued traditional cultural uses among some Indigenous groups.

Below is an interview with Dr. Roland Griffiths, where he explains the Indigenous use of psychedelic plants, including peyote:

Let’s have a closer look at the two mescaline-containing cacti and their use in ceremonial and healing practices in Indigenous cultures.

San Pedro: History and Culture

San Pedro (Trichocereus pachanoi), also known as Huachuma, is a mescaline-containing cacti that is often found in the Andes mountains. The plant has been consumed traditionally by Indigenous cultures, mostly in South America, where the cacti and other plants are prepared as a brew named cimora. The ceremonies with cimora include a curandero (healer) for guiding the experience, as well as, shamanic drumming, singing, and dancing.

Currently, it is illegal to consume San Pedro cacti in the USA, but there are no regulations against growing the plant for landscape purposes. In South American countries, San Pedro is often legal, and many retreat centers offer mescaline journeys for recreational and healing purposes.

Here is an interesting talk from Jorge Ferrer about the use of San Pedro:

Peyote: History and Culture

Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) has been traditionally consumed by Indigenous North American tribes for at least 5,500 years. The crowns of the cacti growing above ground are called the peyote buttons, which are carefully harvested to allow the plant to continue to grow. The cactus is predominantly found in northern Mexico and southwest Texas.

Peyote is central to the religious practices of Wixárika (Huichol Indians) of Mexico and the Native American Church in the USA. In addition to peyote ceremonies, Huichol women are known to consume peyote during pregnancy and after giving birth to stimulate lactation. The effects on breastfeeding are presumed to be from the enhanced release of the hormone prolactin11. However, caution is warranted because controlled research studies have not examined the possible toxic effects of mescaline on the developing fetus or infant.

This video introduces the Huichol people of Mexico and their ritualistic use of peyote:

Tracing back its history19, mescaline has been used as a religious sacrament for at least one hundred years in the USA. The religious use of peyote was formed by the Native American Church in the late nineteenth century in Oklahoma, USA. In 1918, the US government prohibited mescaline use. However, the Native American Church fought for their right to use peyote and succeeded in keeping the sacred cacti as part of their religious ceremonies through the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (and the Amendment in 1994). Today, the church is active and legally able to harvest peyote to use as a sacrament in their religious practices.

This short film documents the use of peyote in the Native American Church:

Within Indigenous contexts, peyote ceremonies are intentionally held for spiritual, psychological, and physical healing. The cacti are believed to balance the body, mind, and spirit to enable personal transformation. Peyote ceremonies often last 10 hours and involve drumming, singing, dancing, social interactions, praying, and processing of deep traumas and personal issues.

In addition, peyote has been medically used for toothaches, rheumatism, asthma, and even cold symptoms. Oftentimes, peyote is believed to cure physiological problems such as animal bites, digestive problems, and chronic pain. In the Tarahumara tribe, peyote is used as a treatment for skin issues.

The video below explains the religious and healing ceremonies with peyote in Indigenous cultures:

Peyote is a central part of many Indigenous communities. Fellows of the Native American Church regularly use peyote in their sacred rituals, ceremonies, and religious sacraments. They utilize this ancestral plant for connection and healing in their community. They grow, harvest, and share the plant in spiritual and respectful ways.

Let’s dive more into the legal status of these plants, and the ongoing discussions regarding the rights to use peyote outside of the Native American Church.

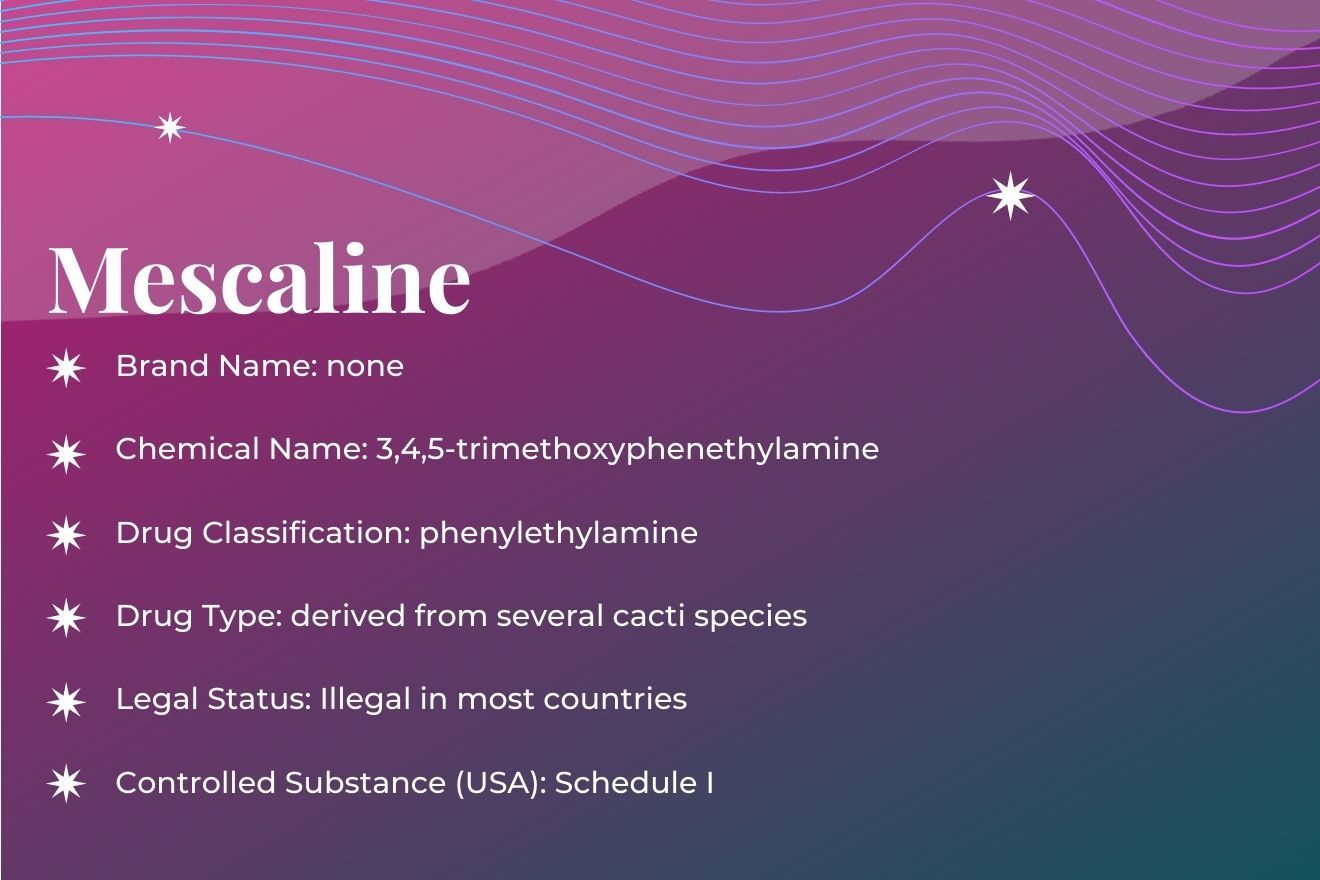

Legal Status: Decriminalization of Peyote

Mescaline is an illegal substance in the UK, Canada, and Europe. In the United States, mescaline is a controlled Schedule I substance under the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances. However, in specific cases, the traditional use of peyote is exempt from religious use, as previously described by the Native American Church.

To reduce prosecution for consuming naturally occurring psychedelic plants and fungi, a movement initiated by the nonprofit Decriminalize Nature started in 2019 in Oakland, California. Many Native Americans have reacted to the decriminalization of peyote. Some say the therapeutic benefits of this sacred medicine should be accessible to everyone who needs it; however, others from Indigenous communities see peyote as a sacred element of their culture and religion. They object to the inclusion of peyote in local and state decriminalization measures because of the growing scarcity of wild peyote and the potential negative impacts on native communities that use peyote in religious ceremonies. Many local initiatives have left peyote out of reform measures in respect for the Native American Church.

Spiritual respect for peyote and the hard-fought legal right to use it are not the only reasons why the Native American community is pushing back on drug reform advocates. Peyote is very slow-growing and only thrives in a small territory of southern Texas and northern Mexico. Over-harvesting peyote is a real threat to the extinction of the plant. It may take 10 or more years for a single peyote cactus to transition from a seedling to the first stage of flowering.

Indigenous people desire to ensure that their culture, identity, and sacred traditions around these plants are protected while psychedelics become mainstream. It is crucial we find ways to build trust and connection with the Indigenous communities and honor their wishes around their ancestral peyote traditions.

Learn more about Indigenous sovereignty and plant medicines, as well as organizations leading the way for conversation and advocacy.

Journalist Michael Pollan stresses the cultural use of peyote in the newly published docuseries “How To Change Your Mind” in the episode “Chapter 4: Mescaline”. The episode focuses on Native Americans’ fight to grow, cultivate, and protect the sacred plant and dives deeper into the decriminalization movement and the potential outcomes for Native Americans.

Pharmacology: What Does Mescaline Do to My Brain?

Mescaline is a long-acting psychedelic substance. The onset of effects typically happens within 45 to 90 minutes of ingestion, with peak effects occurring around two to four hours. The trip often lasts for eight hours, but commonly, the effects are felt for more than 10 to 12 hours in total duration3.

Similar to other psychedelic drugs, mescaline has a strong affinity for the serotonin 2A receptors, which are primarily responsible for inducing the psychedelic experience. “While many psychedelic drugs interact with numerous receptors, their principal and defining activities are mediated by their activation of the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR)”. Mescaline also has a binding affinity for serotonin 1A and 2B/C receptors, as well as alpha2 adrenergic receptors, such as the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1)14,20.

Furthermore, similar to MDMA (and unlike any of the other classical psychedelics that bind to and activate serotonin receptors), it is thought that mescaline may increase the release and/or re-uptake of serotonin4. For this reason, ‘microdosing’ phenethylamines like MDMA (and possibly mescaline) on a regular basis may cause depletion of neurotransmitters and unwanted side effects.

The mescaline experience can be highly visual. People often report seeing colors, patterns, mosaics, spirals, and even animal and human shapes. When scientists began to experiment with mescaline at the end of the nineteenth century, almost all of their work focused on the visual effects2.

Despite its highly subjective nature, the drug-induced imagery has been characterized in great detail by scientists such as Heinrich Klüver, who in 1928 “was the first to recognize that all of the elementary geometric hallucinations induced by mescaline are elaborated variations of four basic forms, which he called form constants: tunnels and funnels, spirals, lattices and checkerboards, and cobwebs”15.

Positive Effects

The positive effects of mescaline are similar to other psychedelic substances. However, due to its unique pharmacology, the mescaline experience is distinguishable from other altered states.

Some of the positive effects of mescaline include stimulation, euphoria, spiritual insights, open and closed-eye visuals, increased positive mood, and altered perception of space and time.

Negative Effects

The risk for side effects highly depends on the person’s mindset and the environment where the journey takes place. Similar to other psychedelics, individuals with certain pre-existing health conditions or who are taking certain medications are at greater risk for side effects. Most negative effects are psychological in nature and may cause distress in the user.

The adverse effects of mescaline include anxiety, paranoia, delusions, psychosis, seizure, and risk of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD).

Physiological Effects

Mescaline experiences begin with intense physical symptoms that may cause discomfort to users.

Here are some of the possible physical side effects of mescaline:

- Sweating and/or chills

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Increased heartbeat

- Increased libido

- Increased blood pressure

- Contracted muscles

- Dilated pupils

- Visual distortions

Psychological and Emotional Effects

The psychological and emotional effects of mescaline greatly vary due to many factors such as dose, set, setting, intention, and more. In medium to high doses, mescaline can initiate insightful experiences, visual alterations, and emotional sensations.

Some of the psychological effects of mescaline include internal and external hallucinations, distortion of time and space, distortion of the physical environment, euphoria, ego death, spiritual insights, tactile sensations, increased emotional sensations, and self-realization.

Contraindicated Medications and Conditions

Mescaline can increase the heart rate and blood pressure21. People with heart conditions or uncontrolled high blood pressure should avoid using mescaline. If you have any health issues, always consult your doctor before taking a psychedelic substance.

Here are some medications that should be avoided with mescaline: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tramadol, blood pressure medications, and immunomodulators.

To reduce the risk of harm and drug-drug interactions16, the following substances should be avoided when taking mescaline: cannabis, stimulants (for example, cocaine and amphetamines), alcohol, and psychedelic drugs classified as tryptamines.

Psychotherapeutic Applications of Mescaline

Mescaline is known to provide spiritual insights, psychological healing, and deep contemplative states22. However, the current research on psychotherapeutic applications is quite limited compared to other psychedelic substances. More clinical trials are needed to investigate the potential use of mescaline for various psychiatric conditions.

Research on mescaline indicates that it may have a high potential for treating anxiety, depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A study from 1974 found peyote was helpful as a treatment for alcoholism17. Another observational study in 2021 demonstrated self-reported improvements in various psychological symptoms after the naturalistic use of mescaline18.

“This report from an online survey study provides detailed information from an international sample of 452 adults who reported improvements in psychiatric conditions following the naturalistic use of mescaline. This is the first international survey study to examine the use of mescaline and its benefits on various psychiatric indices. Results indicate that mescaline use was associated with self-reported improvements in a variety of domains including mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Nearly half of all respondents reported having depression (41%) or anxiety (46%) at the time of their most memorable mescaline use, with a smaller proportion, approximately one-fifth, reporting having PTSD or drug or alcohol misuse or use disorders”18.

Thus, the researchers conclude: “The results from our study indicate that when administered in a naturalistic setting, mescaline may facilitate unintended improvements in self-reported depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance use disorders”.

This talk from Dr. Stacy Schaefer discusses peyote and its potential use for the body and the mind:

Currently, Journey Colab is the only known pharmaceutical company investigating synthetic mescaline. The company is targeting substance use disorders with a combination of mescaline and psychotherapy. Because of the long duration of effects and the associated costs associated with providing patient oversight and therapy, mescaline presents significant challenges to fit into the standard medical model where the ‘work day’ for therapeutic providers typically does not exceed 8 hours. Additionally, the extended experience could be difficult for patients with chronic mental health conditions, especially if the journey is psychologically challenging.

Literature on Mescaline

Mescaline has a prolific presence in psychedelic literature. Many books have been written about mescaline, where authors describe their forays into the mind-bending experiences with mescaline. Our knowledge of mescaline is heavily influenced by these accounts:

The author of the book, Jean-Paul Sartre, is one of the first to have a life-changing mescaline trip and go on to write about it. Although the book is not entirely about his mescaline trip, the plant was a great inspiration for his existential writing. After experimenting with mescaline, Sartre believed lobster-like creatures were following him for many years. He included these sea creatures in his novel Nausea, which implicitly quoted his mescaline experience.

The book is written by French writer Antonin Artaud, who shares his extensive experiences with peyote in Mexico.

The novel is an autobiographical story written by Aldous Huxley, where he shares his experiences on mescaline with philosophical implications. Later, the book became one of the most influential pieces of psychedelic literature, and it still remains a classic in psychedelia culture.

Carlos Castaneda writes about the teachings of Don Juan, which involve peyote and rituals.

Plants of Gods is written by ethnopharmacologist Christian Ratsch, who provides knowledge on various psychoactive plants, including mescaline.

Written by Alexander Shulgin and Ann Shulgin, the book describes the science and effects of psychedelic substances, specifically phenethylamines.

Mike Jay provides an extensive review of mescaline and its history.

Scientific Research

The research on mescaline is not as extensive compared to other psychedelic substances. However, some clinical trials and review articles show the potential psychotherapeutic applications of the substance.

Here are some of the selected publications on mescaline:

2005: Psychological and cognitive effects of long-term peyote use among Native Americans

2019: Examination of recreational and spiritual peyote use among American Indian youth

2022: Mescaline: The forgotten psychedelic

Ongoing mescaline clinical trials:

- Comparative Acute Effects of LSD, Psilocybin and Mescaline (LPM)

- Effects of Hallucinogens and Other Drugs on Mood and Performance

References

- Hirschhorn, I. D., & Winter, J. C. (1971). Mescaline and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) as discriminative stimuli. Psychopharmacologia, 22(1), 64-71.

- Hartman, A. M., & Hollister, L. E. (1963). Effect of mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin on color perception. Psychopharmacologia, 4, 441-451.

- Cassels, B. K., & Sáez-Briones, P. (2018). Dark classics in chemical neuroscience: mescaline. ACS chemical neuroscience, 9(10), 2448-2458.

- Dinis-Oliveira, R. J., Pereira, C. L., & da Silva, D. D. (2019). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects of peyote and mescaline: clinical and forensic repercussions. Current molecular pharmacology, 12(3), 184.

- Brunt, T. M., van Genugten, M., Höner-Snoeken, K., van de Velde, M. J., & Niesink, R. J. (2014). Therapeutic satisfaction and subjective effects of different strains of pharmaceutical-grade cannabis. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 34(3), 344-349.

- Hapke, H. J., & Strathmann, W. (1995). Pharmacological effects of hordenine. DTW. Deutsche Tierarztliche Wochenschrift, 102(6), 228-232.

- Vamvakopoulou, I. A., Narine, K. A., Campbell, I., Dyck, J. R., & Nutt, D. J. (2022). Mescaline: The forgotten psychedelic. Neuropharmacology, 109294.

- Bruhn, J. G., De Smet, P. A., El-Seedi, H. R., & Beck, O. (2002). Mescaline use for 5700 years. The Lancet, 359(9320), 1866.

- El-Seedi, H. R., De Smet, P. A., Beck, O., Possnert, G., & Bruhn, J. G. (2005). Prehistoric peyote use: Alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 101(1-3), 238-242.

- Huxley, A., & Schirmer, R. (2015). The Doors of perception. WF Howes Limited.

- Shulgin, A. T., & Shulgin, A. (1991). PIHKAL: a chemical love story (Vol. 963009605). Berkeley, CA: Transform Press.

- Demisch, L., & Neubauer, M. (1979). Stimulation of human prolactin secretion by mescaline. Psychopharmacology, 64(3), 361-363.

- Halberstadt, A. L. (2015). Recent advances in the neuropsychopharmacology of serotonergic hallucinogens. Behavioural brain research, 277, 99-120.

- Cassels, B. K., & Sáez-Briones, P. (2018). Dark classics in chemical neuroscience: mescaline. ACS chemical neuroscience, 9(10), 2448-2458.

- Slocum, S. T., DiBerto, J. F., & Roth, B. L. (2022). Molecular insights into psychedelic drug action. Journal of Neurochemistry, 162(1), 24-38.

- Malcolm, B., & Thomas, K. (2022). Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics. Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1881-1891.

- Albaugh, B. J., & Anderson, P. O. (1974). Peyote in the treatment of alcoholism among American Indians. American Journal of Psychiatry, 131(11), 1247-1250.

- Agin-Liebes, G., Haas, T. F., Lancelotta, R., Uthaug, M. V., Ramaekers, J. G., & Davis, A. K. (2021). Naturalistic use of mescaline is associated with self-reported psychiatric improvements and enduring positive life changes. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), 543-552.

- La Barre, W. (1979). Peyotl and mescaline. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 11(1-2), 33-39.

- Kolaczynska, K. E., Luethi, D., Trachsel, D., Hoener, M. C., & Liechti, M. E. (2022). Receptor interaction profiles of 4-alkoxy-3, 5-dimethoxy-phenethylamines (mescaline derivatives) and related amphetamines. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 3748.

- Neumann, J., Azatsian, K., Höhm, C., Hofmann, B., & Gergs, U. (2023). Cardiac effects of ephedrine, norephedrine, mescaline, and 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in mouse and human atrial preparations. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 396(2), 275-287.

- Uthaug, M. V., Davis, A. K., Haas, T. F., Davis, D., Dolan, S. B., Lancelotta, R., … & Ramaekers, J. G. (2022). The epidemiology of mescaline use: Pattern of use, motivations for consumption, and perceived consequences, benefits, and acute and enduring subjective effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(3), 309-320.